“The art of Jiu-Jitsu is worth more in every way than all of our athletics combined.”

These inspiring and true words were written in 1905 by President Theodore Roosevelt, a war hero, Medal of Honor recipient, and Nobel Peace Prize winner who was also an honorary 8th dan judo black belt, awarded posthumously by the United States Judo Association in 2007. Of course, most know him as the 26th President of the United States.

President Roosevelt was a mixed martial artist.

As a competitive amateur boxer training primarily under former prizefighter John Long and former middleweight champion Mike Donovan, and training in wrestling under American Middleweight Champion Mike J. Dwyer, the president was no stranger to combatives. In his autobiography, he recalls being a “sickly boy,” having a smaller-than-average build, severe asthma, and lacking athletic ability, often being bullied by bigger and stronger children, recalling that boys his age would assess him as a “foreordained and predestined victim.” After reading books and historical accounts of great American military leaders, TR desired to become more formidable. At 14 years old, he began his lifelong journey in combat arts (Roosevelt, 1914).

In 1904, while hosting a Japanese delegation at the White House, President Roosevelt was impressed by a Japanese Jiu-Jitsu demonstration led by Yoshiaki Yamashita. Yamashita, one of the earliest and highest-ranking judokas in Japan and part of the elite “Shitennō,” or Four Guardians of the Kodokan tasked with propagating the martial art in the West, much like Mitsuyo Maeda did in Brazil a decade later in what would transform into Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (Special Collections and University Archives, 2008). Soon after, Yamashita moved to the United States, where he held private lessons for the president. The president’s Judo training included grappling elements, ground control, and submissions, such as joint locks and chokes (Roosevelt, 1904/1919). It is noted that during this time, Judo and Japanese Jiu-Jitsu were terms often used interchangeably.

Visiting the president? Bring your gi.

President Roosevelt roped everyone into training with him. Not only did he get his kids involved in jiu-jitsu, but historians note he also persuaded many others to train with him, including his private secretary, the Japanese naval attaché, Secretary of War William Howard Taft, Secretary of the Interior Gifford Pinchot, his wife, and his sister-in-law (Clark, 2015; Drapkin, 2007; Svinth, 2000).

Robert Johnstone Mooney, a respected writer at the time, recalls visiting the White House on business, but the meeting quickly turned into a grappling match. He recounts President Roosevelt saying, “By the way, do you boys understand jiu-jitsu …you must promise me to learn that without delay. You are so good in other athletics that you must add jiu-jitsu to your other accomplishments. Every American athlete ought to understand the Japanese system thoroughly” (1923).

President Theodore Roosevelt was one of us.

Like all of us who train in jiu-jitsu, President Roosevelt was once a beginner, displaying many novice behaviors and making the typical mistakes.

The Spazzy White Belt

President Roosevelt was a strong man. At only 5’10” but weighing 220 pounds, he was once described as “over-engined” and physically felt like “two strong men combined” (Morris, 1981). Like many beginners, the president struggled using technique in favor of strength. Professor Yamashita once stated that although President Roosevelt was his “best student,” he was “very heavy and impetuous, and it had cost the [him] many bruisings, much worry and infinite pains during Theodore’s rushes to avoid laming the President of the United States” (Clarke, 1914). Professor Yamashita was a fantastic and patient teacher, but, by all accounts, President Roosevelt was a spazzy white belt.

The president wanted to impress others with his training.

No Thanksgiving dinner is complete without a “Hey, check out what I can do” moment, and President Roosevelt was no different. The willing or unwilling, the interested, and the disinterested, it did not matter to the president because he was going to show them anyway. Like most new practitioners, he wanted to show off his skills to family and friends, in hopes it would inspire them to train.

President Roosevelt would dress in one of his gis and demonstrate his favorite technique, the Seoi Nage, or “Suit Throw,” as he called it, on hapless visitors who were undoubtedly visiting the White House for any reason other than to train in martial arts (Mooney, 1923).

The president’s desire to show off his training seemed to have no limits, as he once grew restless during a luncheon with the Swiss Minister Fernand Du Martheray and decided to demonstrate jiu-jitsu techniques. To the shock of other attendees, President Roosevelt grabbed the minister and “executed a jiu-jitsu hold that landed the minister on the floor,” which delighted the guests and the minister himself with “roars of laughter” (Svinth, 2000).

Obsession

Early in a practitioner’s jiu-jitsu journey, many are obsessed with the nuances of the martial art, focusing on the influence of technique, strength, size, and athleticism, as well as the benefits of incorporating other combat arts. President Roosevelt was no different, and it was not uncommon for him to host training partners of different dispositions and contemplate the results. After one such training session, he recalled:

“Yesterday afternoon we had Professor Yamashita up here to wrestle with [Joseph] Grant [a catch wrestler]. It was very interesting, but of course jiu jitsu and our wrestling are so far apart that it is difficult to make any comparison between them. Wrestling is simply a sport with rules almost as conventional as those of tennis, while jiu jitsu is really meant for practice in killing or disabling our adversary. In consequence, Grant did not know what to do except to put Yamashita on his back, and Yamashita was perfectly content to be on his back. Inside of a minute Yamashita had choked Grant, and inside of two minutes more he got an elbow hold on him that would have enabled him to break his arm; so that there is no question but that he could have put Grant out. So far this made it evident that the jiu jitsu man could handle the ordinary wrestler. But Grant, in the actual wrestling and throwing was about as good as the Japanese, and he was so much stronger that he evidently hurt and wore out the Japanese. With a little practice in the art I am sure that one of our big wrestlers or boxers, simply because of his greatly superior strength, would be able to kill any of those Japanese, who though very good men for their inches and pounds are altogether too small to hold their own against big, powerful, quick men who are as well trained” (Roosevelt, 1904/1919).

The president had excuses to skip training, but trained anyway.

While president and leader of the free world, TR was married and raising six young children. He was injured, older, trying to maintain an ambitious training schedule, and battled fatigue. TR wrote, “I am wrestling with two Japanese wrestlers three times a week. I am not the age or the build one would think to be whirled lightly over an opponent’s head and batted down on a mattress without damage. But they are so skillful that I have not been hurt at all. My throat is a little sore, because once when one of them had a strangle hold I also got hold of his windpipe and thought I could perhaps choke him off before he could choke me. However, he got ahead” (Roosevelt, 1904/1919).

I am very glad I have been doing this Japanese wrestling,” the president once said, “but when I am through with it this time I am not at all sure I shall ever try it again while I am so busy with other work as I am now. Often by the time I get to five o’clock in the afternoon I will be feeling like a stewed owl, after an eight hours’ grapple with Senators, Congressmen, etc.; then I find the wrestling a trifle too vehement for mere rest. My right ankle and my left wrist and one thumb and both great toes are swollen sufficiently to more or less impair their usefulness, and I am well mottled with bruises elsewhere. Still I have made good progress, and since you left they have taught me three new throws that are perfect corkers (Roosevelt, 1904/1919).

With the countless training obstacles the president faced, similar, but on a much larger scale, to what every jiu-jitsu practitioner faces, he continued training and found satisfaction in his progress. That said, like many practitioners, he was unable to continue formal training with Professor Yamashita, likely due to his reelection campaign, the construction of the Panama Canal, and his influential role in mediating the Russo-Japanese War, earning him the Nobel Peace Prize, and overseeing the expansion of the United States Navy to become a naval superpower.

Law Enforcement Influence

The president was not only a strong advocate for law enforcement, but he proudly served as a deputy sheriff in the Dakota Territory and as the New York City Police Commissioner, where he led anti-corruption efforts. In 1908, President Roosevelt created the Bureau of Investigation, which would later become the Federal Bureau of Investigation, to handle federal crimes (Oliver, 2019).

As the New York City Police Department (NYPD) Commissioner, he advocated for officers to practice boxing and wrestling. He procured boxing equipment, established a boxing club for officers, introduced mandatory firearms and physical training, and conducted surprise fitness-for-duty inspections. These initiatives influenced modern police training and emphasized physical tactics for officers (Roosevelt, 1913; Svinth, 2003).

The president’s legendary success as former NYPD Commissioner was massively influential on later commissioners, including William McAdoo, who became commissioner in 1904 after Roosevelt vacated the position in 1897 (Beekman, 2013). In response to an epidemic of police brutality and excessive force claims, McAdoo relied heavily on President Roosevelt’s emphasis on physical tactics training, ethical policing, and interest in jiu-jitsu, stating, “I have been thinking for some time of having the police taught the Japanese art of self-defense… It would give a small man the advantage over a big one, and often save the use of the club” (Beekman, 2013; “May Teach Police Jiu-Jitsu,” 1905).

McAdoo ordered that jiu-jitsu be tested at the NYPD headquarters to determine if the martial art would be a viable means of restraining and controlling large, strong, and physically resistant subjects (Beekman, 2013). He selected his toughest, largest officers to face off against a much smaller Japanese jiu-jitsu instructor. Despite the much larger officers attempting to crush the much smaller Japanese man, he reportedly threw them effortlessly, using their own momentum against them (Beekman, 2013; “May Teach Police Jiu-Jitsu,” 1905). McAdoo concluded, “I have no doubt that jiu-jitsu is a good thing. It would give a small man the advantage over a big one, and often save the use of the club” (Beekman, 2013; “May Teach Police Jiu-Jitsu,” 1905).

Once President Roosevelt ascended to the highest office and began his jiu-jitsu training, he advocated for its inclusion in military education, specifically in the U.S. Naval Academy, viewing it as superior self-defense. While President Roosevelt did not introduce jiu-jitsu to the NYPD, one of his early jiu-jitsu instructors, John J. O’Brien, a police inspector, was influential in spreading the martial art to law enforcement (Svinth, 2003).

President Roosevelt’s jiu-jitsu training was directly referenced by O’Brien, who was an early advocate of incorporating jiu-jitsu training with police physical tactics. He held demonstrations, wrote books and articles, and authored training manuals to inspire law enforcement officers to train. O’Brien leveraged his connection to the president to advocate for jiu-jitsu as a scientific method of physical training and control, aligning with police needs to restrain suspects without weapons.

O’Brien authored Jiu-Jitsu: The Japanese Secret Science, which later became one of the first commercially marketed references for police physical tactics using President Roosevelt’s name. On the cover, O’Brien prominently claimed he was “Instructor to President Roosevelt,” capitalizing on this known association to validate the text as the “President’s system” (O’Brien, 1905; Svinth, 2003). To his credit, the president even endorsed the training manual, calling it a “first class book” (Roosevelt, 1904).

In a 1904 article in the National Police Gazette promoting jiu-jitsu as a scientific method of using technique and intelligence over brute strength for physical training and self-defense, President Roosevelt’s training was cited as an inspirational example to encourage American men to adopt the art, stating, “The President of the United States is taking lessons in jiu-jitsu, the Japanese system of physical training, and is said to be making good progress in the art. Jiu-jitsu enables a man to use his strength scientifically, and even President Roosevelt is learning it to improve his physical condition.”

“Nothing in the world is worth having or worth doing unless it means effort, pain, and difficulty” (Roosevelt, 1900).

Like the FLEOA 111 Project, President Roosevelt knew that reforming law enforcement agencies and inspiring others to train in jiu-jitsu required hard work and dedication. The FLEOA 111 Project appreciates President Roosevelt’s tremendous contributions to police reform and promoting physical tactics training to law enforcement officers.

REFERENCES

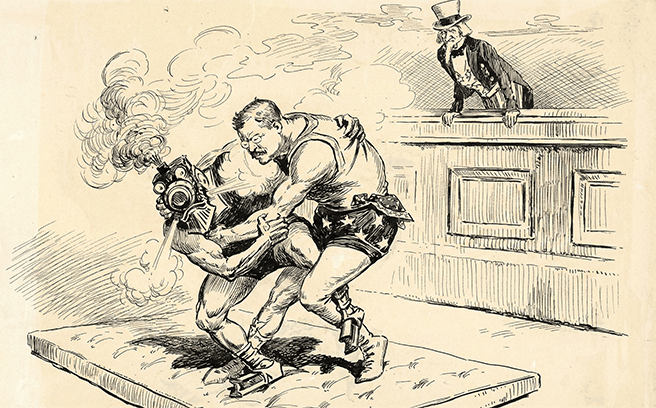

Bushnell, E. A. (1906). Jiu-jitsued [Political cartoon]. Cincinnati Post.

Clark, J. (2015, May 4). The strenuous life: Theodore Roosevelt’s mixed martial arts. VICE.

Clarke, J. (1914, September 27). Men of might are the wrestlers of Japan. The New York Sun.

Consulate-General of Japan in Seattle. (2020, January 23). Through the eyes of the former Consul General Yamada. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

Drapkin, J. (2007, September-October). Theodore Roosevelt: Mojo in the dojo. Mental Floss Magazine.

Edgren, R. (1909). [Illustration of Theodore Roosevelt and Mike Donovan]. In M. Donovan, The Roosevelt that I know: Ten years of boxing with the President and other memories of famous fighting men. B. W. Dodge & Company.

Juley, P. A. (1903). Theodore Roosevelt [Photograph]. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Mooney, R. J. (1923, October 10). My bout with the champion. The Outlook, 135, 311–313.

Morris, E. (1981). Theodore Roosevelt, president. American Heritage, 32(5), 42–48.

O’Brien, J. J. (1905). Jiu-jitsu: The Japanese secret science demonstrated by the Ex. Supt. of Police at Nagasaki. Physicians’ Publishing Co.

Oliver, W. M. (2019). The birth of the FBI: Teddy Roosevelt, the Secret Service, and the fight over America’s premier law enforcement agency. Rowman & Littlefield.

Rogers, W. A. (1905, February 8). Who is master? [Political cartoon]. New York Herald.

Roosevelt, T. (1900). The strenuous life: Essays and addresses. The Century Co.

Roosevelt, T. (1906, February 17). [Letter to Charles J. Bonaparte]. Theodore Roosevelt Papers (Series 2), Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Washington, DC.

Roosevelt, T. (1914). Theodore Roosevelt: An autobiography. Macmillan.

Roosevelt, T. (1919). Letter to Kermit Roosevelt, March 5, 1904. In J. B. Bishop (Ed.), Theodore Roosevelt’s letters to his children. Charles Scribner’s Sons. (Original work published 1904)

Special Collections and University Archives. (n.d.). Yamashita, Yoshiaki, 1865-1935. University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries.

Svinth, J. R. (2000, October). Professor Yamashita goes to Washington. Journal of Combative Sport.

Use your strength scientifically. (1904, July 2). National Police Gazette, 85(1403).

About The Author

Brian Bowers is a Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu black belt under Professor Chris Popdan with 15 years of experience and the Lead instructor of the FLEOA 111 Project. Read More….

Discover more from

The FLEOA 111 Project

Subscribe to our free newsletter to be notified of new articles, events, literature reviews, and other information related to our mission. You do not need to be a member of FLEOA to participate in the FLEOA 111 Project.

Follow The FLEOA 111 Project on social media

You must be logged in to post a comment.